To celebrate Suffrage Day 2017, Councillor Cathy Casey looks at the way the humble bicycle empowered women in New Zealand and assisted in the achievement of women’s suffrage.

Every year on Suffrage Day, Aucklanders gather to celebrate the occasion at the Auckland Women’s Suffrage Centenary Memorial in Te Ha o Hine Place.

The memorial, designed by artist Claudia Pond-Eyley and ceramicist Jan Morrison, was commissioned for the Suffrage Centennial Year in 1993, and is made with more than 2000 coloured tiles.

Over the years there have been several attempts to have the memorial moved or demolished. Each time the women of Auckland have risen up and fought back. The memorial is now protected under the Auckland Unitary Plan and will remain in its current location in perpetuity.

It is a wonderful testimony to our foremothers. It is rich in symbolism and tells the compelling story of how Kiwi women achieved the vote ahead of the rest of the world.

Cycling to the vote

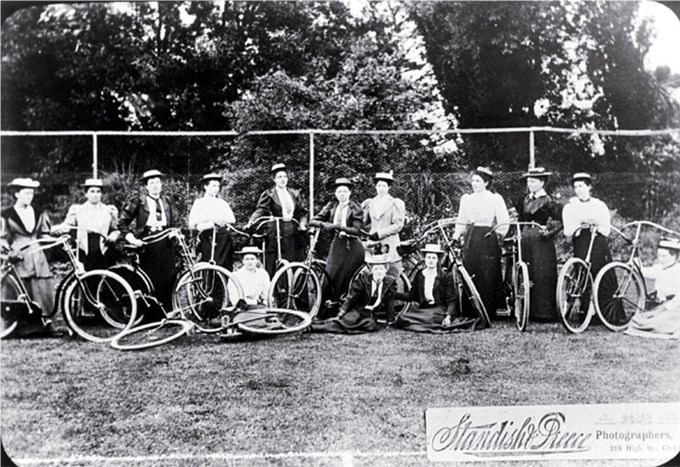

At the top of the stairs there is a panel depicting four cycling women. This panel is not about the individuals depicted – these four are representative of women of the time. Instead, it is about the critical role the humble bicycle played in women’s emancipation in New Zealand.

The bicycle arrived in New Zealand in the 1860s. It offered citizens a cheap means to travel further than by foot, horse-drawn carriage or the expensive and new-fangled motor car.

Early bicycles were known as velocipedes or ‘boneshakers’. They quickly evolved into what we now know as the penny-farthing. While these were popular among wealthy young men, they were dangerously high and lacked efficient brakes or means for women to mount.

It wasn’t until the 1880s, when the safety bicycle with equal-sized wheels was produced, that women seized upon cycling as their new freedom. The safety bicycle’s lower frame and pneumatic tyres made it much more popular for women to ride.

Here at last was an activity that women could do equally with men and which gave them an active recreational interest outside of home and family.

When women took up cycling in numbers, there was an obvious and pressing need for dress reform. Victorian layered skirts were soon replaced with knickerbockers and bloomers and new fashions like the split skirt, similar to today’s culottes.

Wheels of reform

Around the same time as the bicycle enabled women to become more physically and geographically mobile, New Zealand women were also demanding a greater say in the running of the country.

Under the leadership of Kate Sheppard, suffrage campaigners were calling on Parliament to grant the vote to women. They compiled a series of massive petitions and sought signatures up and down the country. What better way for the suffragists to collect them than by bicycle? The memorial panel is testimony to the many miles the suffragists must have ridden on their bicycles to collect many of the 32,000 signatures that secured women the vote.

The 1893 Women's Suffrage Petition comprised 546 sheets of paper, glued together to form one continuous roll, 274 metres long. The roll is now preserved at the National Library of New Zealand in Wellington. The international significance of the document has been recognised by its inclusion in the UNESCO Memory of the World register of documentary heritage.

The personal and the political

Just as the suffragists were organising politically, so women cyclists were organising socially. In 1892, the first all-women cycling club in Australasia was founded in Christchurch. The Atalanta Ladies' Cycling Club organised picnics, day trips and tours to encourage women into cycling. It proudly boasted Kate Sheppard as one of its members.

Today, when I park my electric bike next to the memorial’s four women cyclists, I acknowledge the bicycle’s contribution to women’s emancipation. In the words of the nineteenth century American women’s rights activist Susan B. Anthony: “Bicycling has done more to emancipate women than anything else in the world…I stand and rejoice every time I see a woman ride by on a wheel …the picture of free, untrammeled womanhood.”

Not a bad legacy for cycling!