Kākahi, the native freshwater mussels that once thrived in the depths of Lake Rototoa, are facing a grim future.

Recent surveys reveal 85 per cent of the mussel population in the lake has perished, raising alarm bells for the future of this valued lake ecosystem.

The kākahi play an essential role in maintaining the lake's health by filtering water, oxygenating sediment and creating habitats for other native species.

Frame for breeding kākahi in Lake Rototoa

According to a recent survey conducted by Aotearoa Lakes divers, of the 2,238 mussels counted, an alarming 1,894 were found dead. Worryingly there was no evidence of younger size classes indicating there has been no recent recruitment to the population.

Policy and Planning Committee Chair Councillor Richard Hills has expressed his concern about the dire situation.

“The rapid decline of kākahi in Lake Rototoa is not just a loss of a native species, but a signal of an ecosystem in crisis.

“These mussels are the lake's natural filter, vital for maintaining water quality and supporting other native species. Without them, we risk seeing water quality deteriorate rapidly.

“If we don’t act now, Lake Rototoa could lose this precious native species and this will have an impact on lake biodiversity,” said Hills.

Kākahi are known as a “keystone species,” meaning their presence and health are integral to the ecosystem. They filter large amounts of water, removing algae, microorganisms, and even bacteria, which supports the overall health of the lake.

The decline in their population signals an urgent need for intervention, as the mussels help prevent algal blooms and contribute to the well-being of other native species, including kōura (freshwater crayfish), bullies, and native fish.

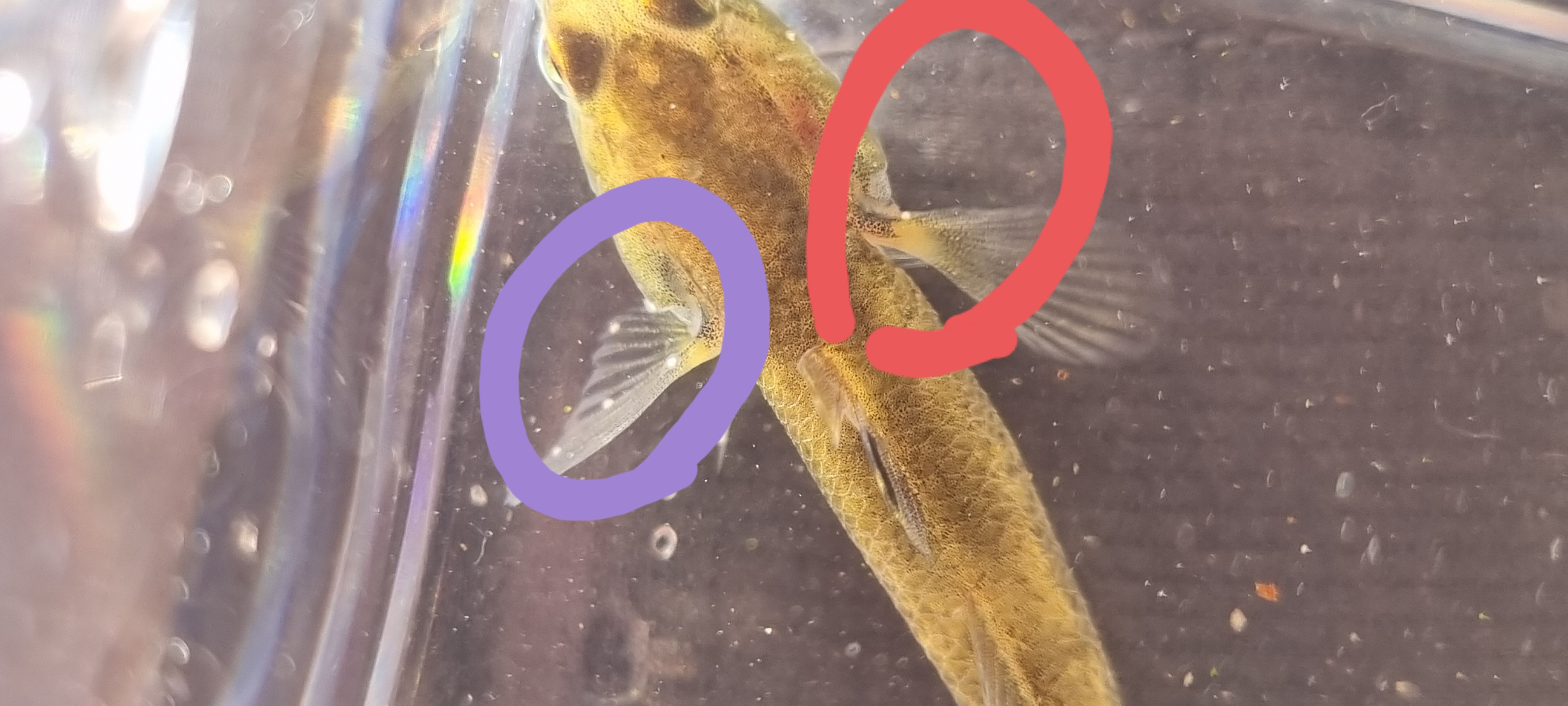

Freshwater bully with kākahi larvae attached (ringed).

Auckland Council’s Senior Freshwater Biosecurity Advisor, Belinda Studholme, stressed the importance of protecting the lake and its biodiversity.

"Lake Rototoa is a taonga for Auckland.

"The kākahi are not only a vital part of the lake's ecosystem, but they also hold deep cultural significance for Māori as a taonga species. Without them, we risk losing both a natural biofilter and an important part of our heritage."

To prevent the extinction of kākahi in the lake, the project team, funded by Auckland’s Natural Environment Targeted Rate, has been testing innovative interventions.

“We’ve built enclosures designed to protect kākahi beds from pest fish, allowing the native bullies to interact with the mussels and encourage successful breeding. Initial trials have been promising, with juvenile kākahi successfully developing in these enclosed areas.

“If we can replicate this on a larger scale, we may be able to reverse the decline,” adds Studholme.

Pollution, pest fish, and declining water quality are believed to be the primary drivers of the kākahi decline.

When it rains contaminants and sediment from the land are carried into the lake, while invasive freshwater plants and fish destroy the natural habitat of the mussels. Furthermore, algal blooms can overwhelm and suffocate kākahi, exacerbating the situation.

Despite ongoing water quality monitoring since the 1980s, the devastating collapse of the kākahi population went undetected until recently. To address this issue Auckland Council is studying the lake's biodiversity to develop solutions to save this vital species.

"We're racing against time to understand the reasons behind this extreme die-off and find solutions to encourage kākahi survival. The kākahi’s ability to filter water and maintain the lake's ecosystem is irreplaceable. Protecting Lake Rototoa’s kākahi isn’t just about saving a species—it’s about preserving the entire ecosystem for future generations,” adds Hills.

Efforts are now focused on identifying the factors behind this decline and taking action to restore the lake’s balance. The stakes are high; without intervention, Lake Rototoa could face further biodiversity losses, with long-term impacts on lake health.